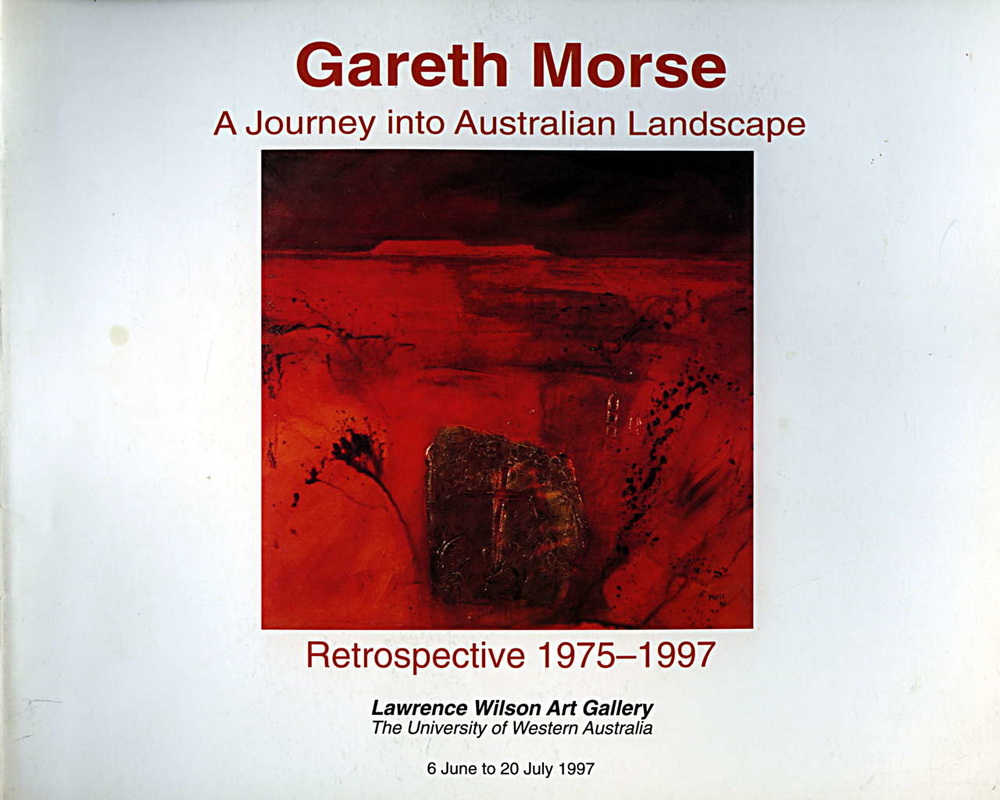

Gareth Morse

A Journey into Australian Landscape

Retrospective 1975-1997

Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, The University of Western Australia

6 June to 20 July 1997

"Art pierces the veil and gives sense to a notion of reality which lies beyond appearance" - Iris Murdoch

|

In 1975 Gareth Morse arrived in Perth to take up a position as a lecturer at the Art Education Department, Mount Lawley College of Advanced Education. Bom in Rhondda, Wales in 1932 and educated in the United Kingdom, he was already an experienced artist who had been working as both an artist and teacher for nearly twenty years when he arrived in Australia.

His methods of working and intellectual approach to his subject matter were already well evolved before his arrival here. To arrive in a new country and to try to paint the landscape is a challenge. On the one hand it requires boldness and on the other a sense of the cultural distance involved. Yet the work completed since settling in Australia is so inextricably linked to this geographic locality, to a sense of space and vastness, isolation and harshness, that it is difficult to contemplate how differently his work would have developed had he remained in lusher and more populous surroundings. Even the relative paucity of softness and fecundity of the Western Australian coastline and south west region did not sustain his artistic interest for long. The need to record the unfamiliar landscape in this early period after arriving in Australia, seems to have initiated a major reassessment of how best to respond to the whole process of making art here. The result was a show of 35 works in his first solo exhibition in Perth in 1976, representing a very prolific period in the artist's career.1 In Quarry Pool and Toodyay Road I he sees the unfamiliar colours of the landscape and experiments with how to represent a vast landscape which is often repetitive, or at least lacking an obvious picturesque focus. |

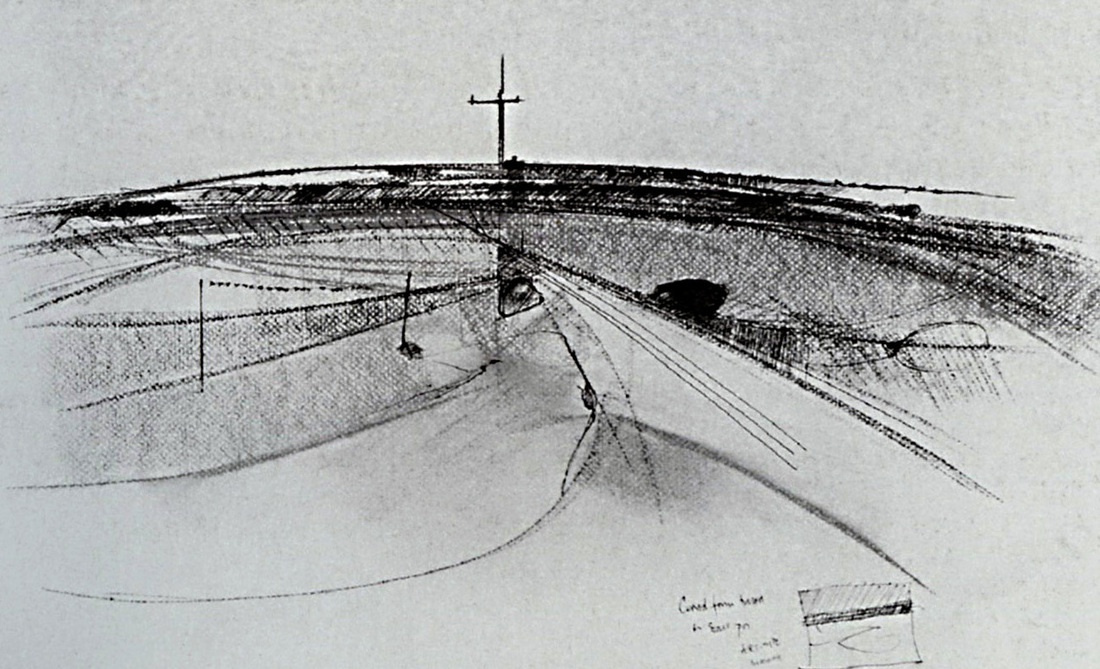

I don't think about space--it's inevitable, if you are in a big landscape, a two-thirds horizon (which I'm fond of) is there. The unpainted paintings are just extensions to the left and right of what I've painted.2

The Coast series from this exhibition, is a good example of this approach. A view of the coast was divided into five sections and each portion then painted as separate works which were hung together for the duration of the exhibition, but sold as individual paintings. In each work, the same elements of sky, sand and water appear as a continuum, but the glowing pale golds and creams of the beach and luminous blues of the ocean flecked white from the wind and spray, represent the infinite variety of nature and clearly show the artist's concern to represent mood in a semi-abstract form using colour and structural manipulation. In 1976 Morse began a series of journeys which were to become the basis for all his future work. He sought out landscapes that were distinctive largely because of their intractable resistance to a European vision, whether industrial, post-industrial, remote or hazardous. Occasionally he accompanied the family, but increasingly the journeys became a solitary pursuit. This aspect of the joumeys and the sense of isolation and loneliness it engendered, became an essential element of the artist's approach to painting. Since 1979, when Morse first visited Kalgoorlie, the Goldfields area has been the central site of his artistic practice. Many trips to this area followed and the artist continues to paint his visions of this area even in his most recent work. Something in the desolate nature of this land seemsto satisfy his need for contemplation and enables him to respond creatively to the landscape. |

|

Many other journeys have covered areas as diverse as Cervantes and the Pinnacles, Dampier, Karratha and Tom Price in the Pilbara, Darwin, Katherine Gorge, Kakadu and Kununurra, the Bungle Bungle Ranges, Ord River and Birdsville, Thursday Island and Cape York. All these destinations invoke the universal in their scope and in the absence of humanity, although they often show evidence of the traces of past lives.

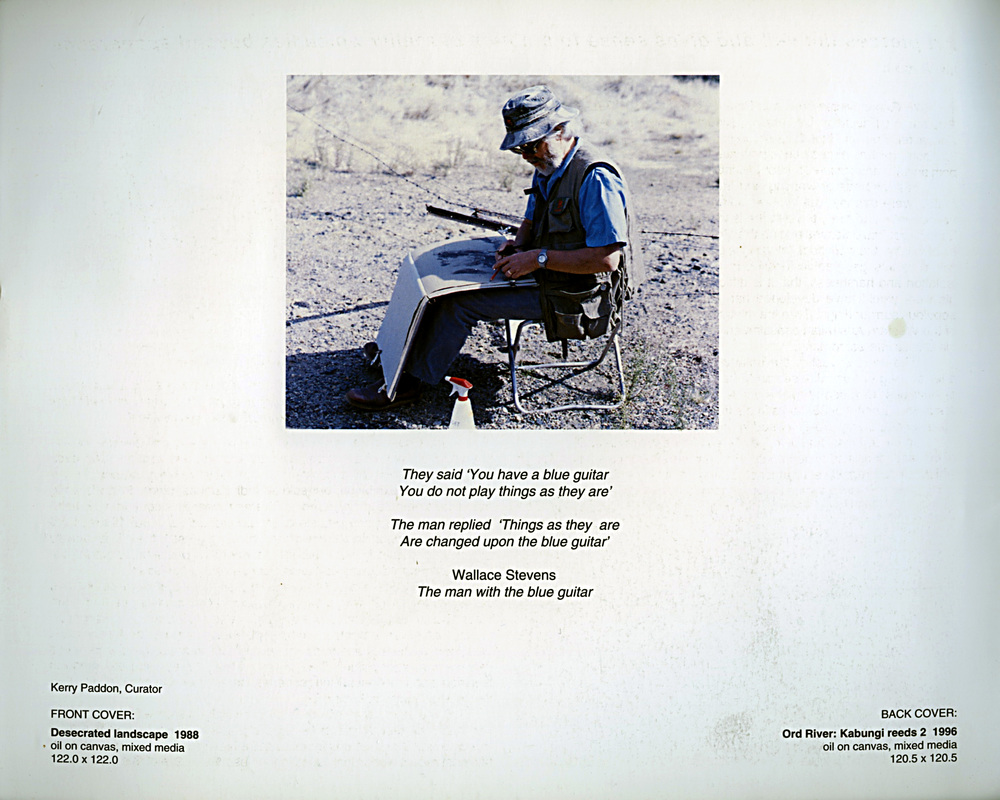

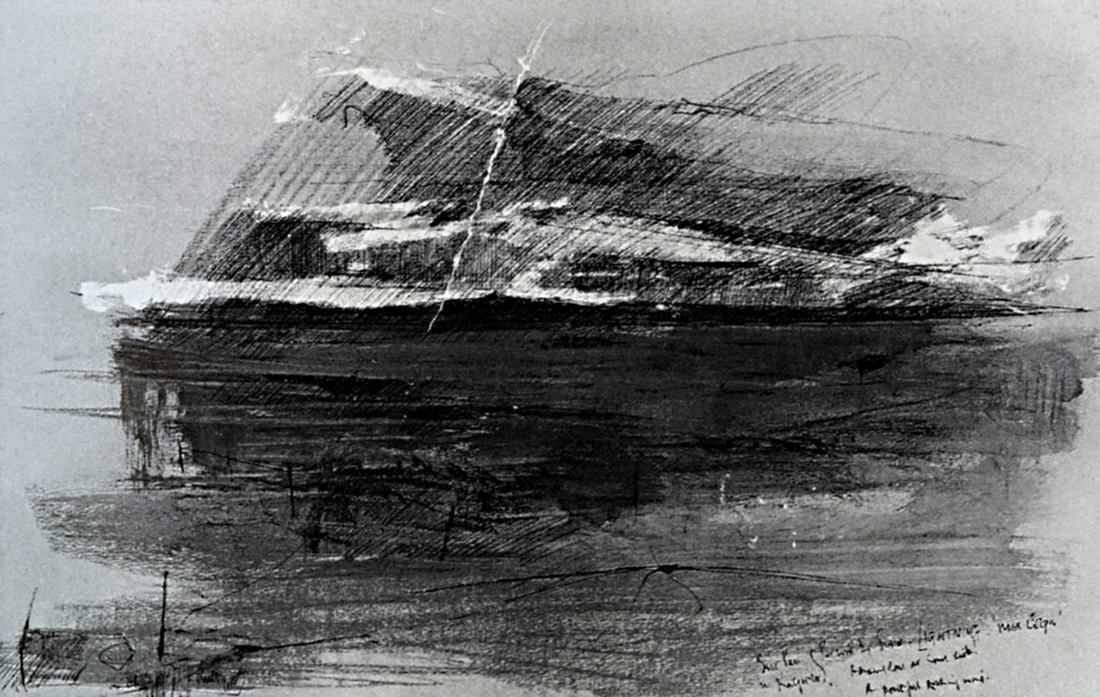

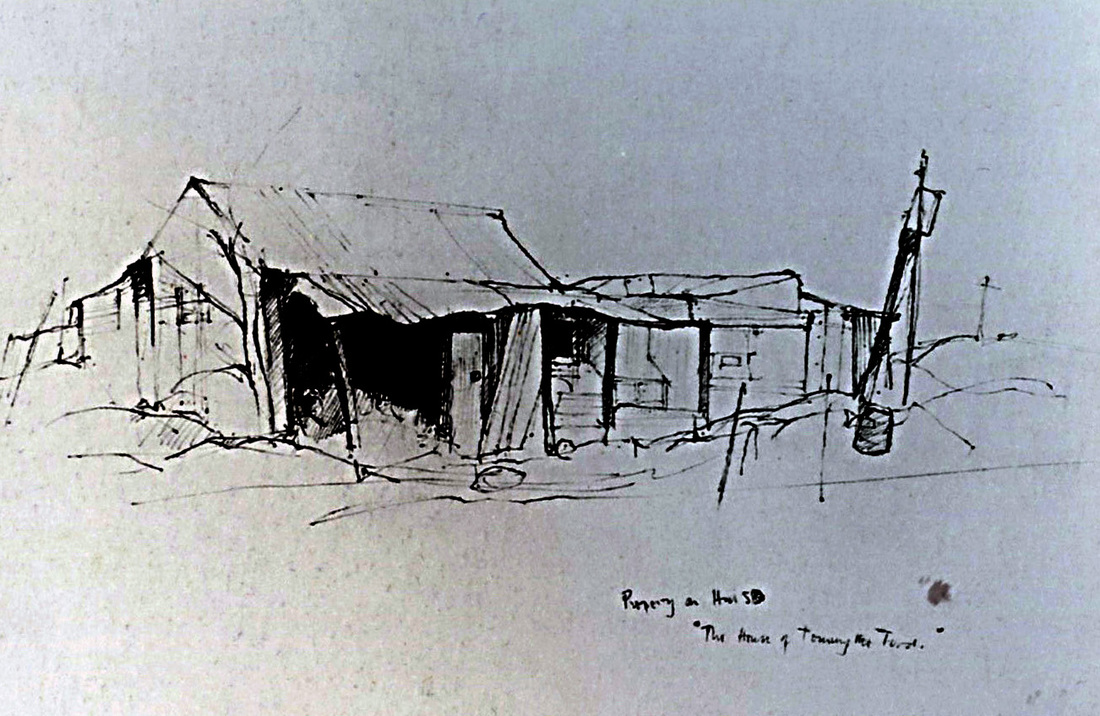

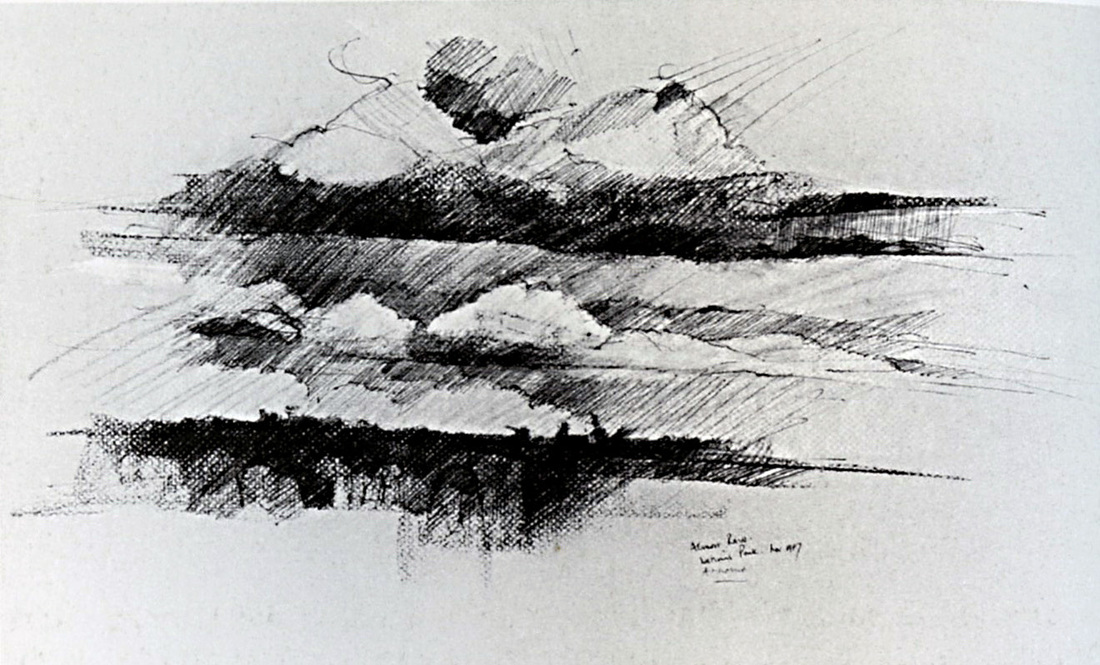

The viewer experiences a sense of heightened awareness of the hardship and transient aspects of life, through confrontation with the infinite nature of the universe represented in Morse's landscapes. Gareth Morse takes journeys into the landscape, but not to faithfully record the minutiae of a scene. He does not paint in the landscape. He travels to experience the land in all its aspects; the isolation, the historical resonance of a place, its scars and physicality and often the degradation created by man; the smells, the light, the wildlife, the heat. He records the landscape in detailed drawings, which are very straight-forward, realistic renditions, but they do not provide the basis for his paintings in any real sense. Instead the subjects of his paintings emerge from the process of reviewing his sketchbook drawings. They do not equate with the drawings. They are in no sense a working up of the drawings into paint. They are more akin to visual keys; as if on reviewing the drawings, the artist can relive the whole experience of being at that place, the atmosphere, his mood and thoughts, in the same way that a particular smell can sometimes transport us back to a childhood experience. |

Drawing is very clear to me-- I know that's that and I draw it. It's not a bit like painting. Without doing it, I can't see the landscape, but there is no one-to-one match with painting. Drawing is a source of know~edge - then it's a process of osmosis.3

|

The impulse to truth is greatly more than the underestimated issue of fidelity to appearance. The act of drawing is for me a way through this difficulty, through unequivocal attention to the particular. If this is the Hotel at Agnew, a God forsaken hole if there ever was, then let my drawing be identifiable, recognisable by others who have been there as the Hotel at Agnew. So that the identifiable place is the first stage of more evolved realisations. Behind the whole is the issue of reality itself.4

If the act of drawing for Morse is straight-forward and meticulous, then painting is a much more physical and robust occupation.

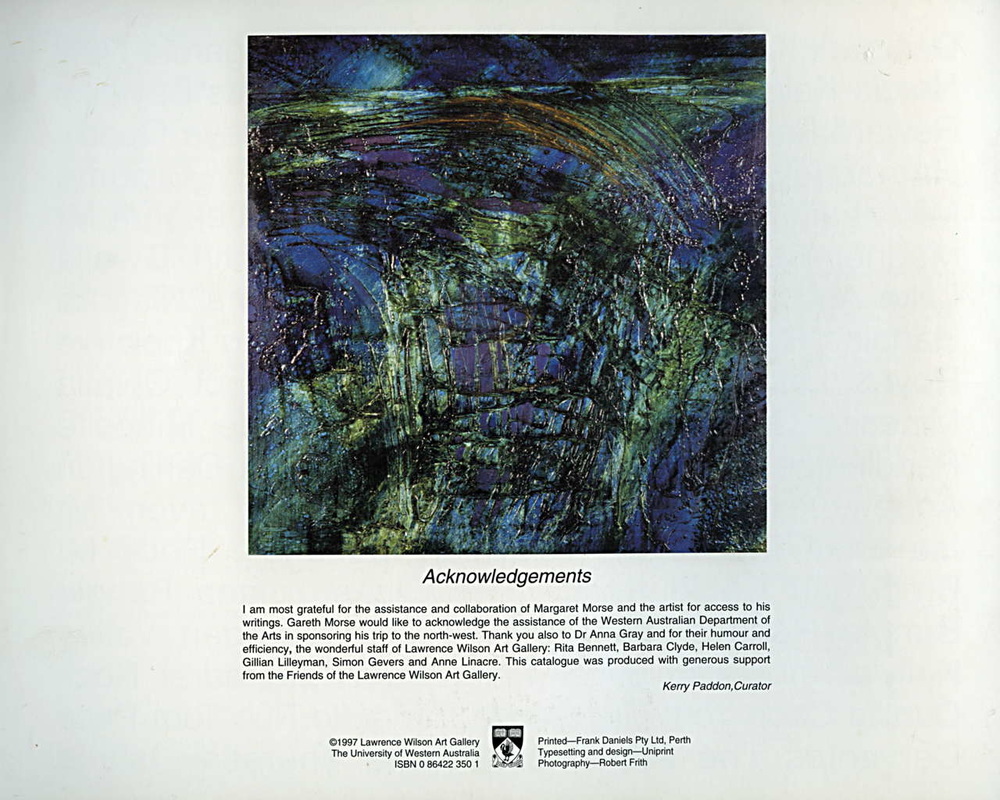

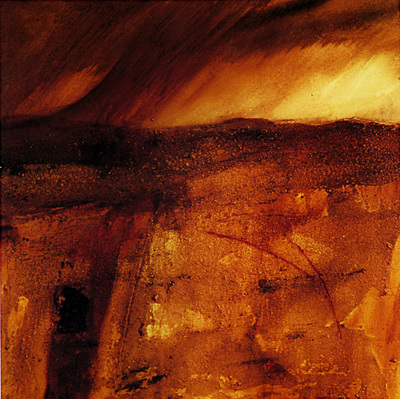

With the canvas placed horizontally on four milk crates the artist works around the canvas, layering the paint and often tilting the canvas to allow it to drip, then incorporating other elements such as sand from the region he is painting and toupre. In Ord River: Rain storm and Ord River: Kabungi Reeds I and II, all painted in 1996, the fluidity of the dripping paint is used to encapsulate the watery subject of the paintings. Fluidity combined with the density of colour and strong dark incisions into the surface of the paint in Ord River: Kabungi Reeds II, results in the work glowing with an opalescent translucency which defies certainty of identification.

Is the viewer looking into water or mineral?

More recently I've been concerned with the density of sensation - looking at rivers, looking into rivers. I found the Ord quite remarkable.5

If the act of drawing for Morse is straight-forward and meticulous, then painting is a much more physical and robust occupation.

With the canvas placed horizontally on four milk crates the artist works around the canvas, layering the paint and often tilting the canvas to allow it to drip, then incorporating other elements such as sand from the region he is painting and toupre. In Ord River: Rain storm and Ord River: Kabungi Reeds I and II, all painted in 1996, the fluidity of the dripping paint is used to encapsulate the watery subject of the paintings. Fluidity combined with the density of colour and strong dark incisions into the surface of the paint in Ord River: Kabungi Reeds II, results in the work glowing with an opalescent translucency which defies certainty of identification.

Is the viewer looking into water or mineral?

More recently I've been concerned with the density of sensation - looking at rivers, looking into rivers. I found the Ord quite remarkable.5

|

Some of the artist's first works after arriving in Australia were painted with acrylic paint, but later works are almost always oil paints on stretched canvas or hardboard with other media incorporated to add texture to the surface of the work, in the manner of the Spanish artist, Antonio Tapies, whose work Morse greatly admires.

The addition of the earth and other tactile materials acts to reveal reality as the artist understands it, through the direct sensation of the particular substance.The addition of such organic souvenirs of his joumeys creates new objects charged with sensation and ambiguity. In some cases such as Horseshoe, Niagara the souvenir is literal. The horseshoe in the painting was picked up by the artist at the site and its image incorporated as a reminder of the human presence in an area long since abandoned to the elements. In Crocodile tracks, Kakadu the sand added to the pigment creates a composition which could be a view of the outback from an aerial viewpoint rather than a closely observed encounter with crocodile tracks in the sand. Morse's paintings can often be interpreted as having an ambiguous viewpoint that would allow the work to be seen in both these ways--both as macroscopic and microscopic. Often the scale is of little importance to the experience and mood of the landscape depicted. Sometimes the primary layers of paint appear as a stain on the canvas but it is usual for the paint to be thickly layered in at least some areas, much as the elements in the landscape are built up as a gradual process over time. Landmarks and creek, East Kimberley is an example of this process. Layers of paint are built up into ridges on the surface of the work, punctured with slivers of electric turquoise pigment and then heavily glazed. The result appears as an aerial view of an ancient formation, a map of the landscape which reflects the elemental forces which made it. In Salt pans, Dampier, the cracked surface of the painting is analogous with the fracturing of the landscape forms. In his search for a distinctive landscape, the artist is attracted by extremes -extremes of heat, distance and isolation, geological time, colour and landmass. Gentle lush landscapes are of no interest to him, hence his powerful fascination with the landscapes of the northern and eastern areas of Western Australia. |

I have at times seen [the Australian landscape] in very romantic terms,, notably my paintings of the Goldfields; that romanticism is tied to my boyhood and early years as an artist in South Wales.6

|

Growing up in a mining area, Morse understands the hardship of the lives of the pioneer miners and the despair implicit in their often futile search for riches. He sees their lives as representing human effort on an epic scale. But it would be inaccurate to suggest that Morse's work predominantly exists within the realm of the romantic notion of the Australian bush as harsh and isolated, a place for heroes. While acknowledging the history of mythologising the outback and conceding that his own response to these landscapes contains elements of tragedy and romanticism, in essence his approach to the hardships of the land is both more spiritual and more intellectual. He strives to create a means to translate the landscape and its inherent metaphors into a physical language of paint to communicate the experience of the journey to the viewer. The resolution of the experience of the landscape lies in the tension or balance between the experience and its mood resolved through colour. |

Pictorial organisation or preconceived structures are a convention to be disregarded. The order lies behind experience but to proceed requires both a meditative and a physical act.7

|

In 1988, Morse completed a series of paintings including Desecrated Landscape, Kalgoorlie and Old Bucket, Kanowna, which graphically illustrate his use of mood and colour, together with simple indexical forms, to create works of subtlety and complexity.

Like the paintings of Rothko, they are infused with emotion. The artist strives to reveal something of both the physical landscape and the landscape of the spirit and to achieve harmony and equilibrium between the two. These dark, brooding paintings representing the abandoned detritus of lives past, glow with an unextinguished flame of life spirit. The becomingness of the world, manifested in such paintings is to me the truth of experience and I cannot separate this from my notion of God. It is the landscape of the spirit which I seek.8 - Kerry Paddon, 1997. Curator, Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, University of Western Australia |

|

1 'Gareth Morse' Undercroft Gallery, The University of Westem Australia, Perth, 6-15 April 1976.

2 Gareth Morse, Notes on Painting unpublished notes, 1996, p.1.

3 ibid, p.3.

4 Gareth Morse, Fragments: Essays on Art and Life unpublished notes, 1993, p.6.

5 op cit, Notes on Painting, p.1

6 ibid, p.1

7 op cit, Fragments, p.9

ibid, P.10.

2 Gareth Morse, Notes on Painting unpublished notes, 1996, p.1.

3 ibid, p.3.

4 Gareth Morse, Fragments: Essays on Art and Life unpublished notes, 1993, p.6.

5 op cit, Notes on Painting, p.1

6 ibid, p.1

7 op cit, Fragments, p.9

ibid, P.10.

Note: this is a web version of the original 1997 Catalogue available here:

1] National Library of Australia Catalogue Link

2] Scanned PDF - including complete catalogue of exhibited works:

1] National Library of Australia Catalogue Link

2] Scanned PDF - including complete catalogue of exhibited works: